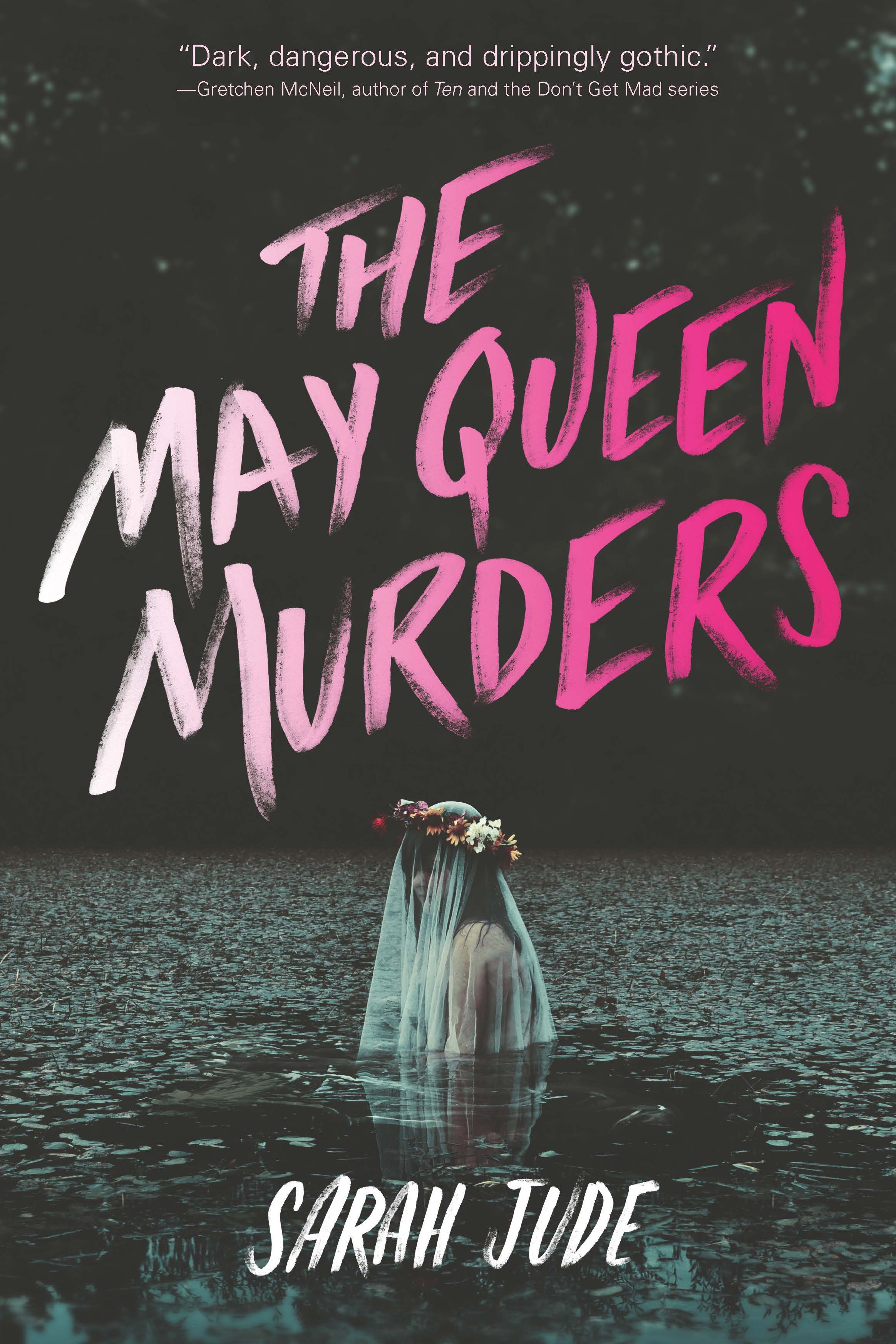

Sarah Jude

Midwestern Gothic Author & Artist

The May Queen Murders

Book Details:

Release Date: May 3rd, 2016Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt - HarperCollins Publishing

Paperback ISBN-13: 9780544640412

eBook ISBN-13: 9780544937253

Two girls: one with a secret, one with a promise that she’d uncover it.

Welcome to Rowan’s Glen—a place full of old fashioned superstition and secrets. Twenty-five years back, a teenage girl was murdered after being crowned queen at the Glen’s May Day celebration, and outsiders have regarded the isolated farming community with suspicion ever since.

But that was before Ivy Templeton was even born. She’s lived in Rowan’s Glen for all of her sixteen years, and feels safe there with the company of her free-spirited cousin Heather, and their friend, Rook, son of the sheriff.

Until . . . animals start showing up dead, clearly from unnatural means. Dark omens seem to appear everywhere Ivy goes. And Heather, who used to tell Ivy everything, is sneaking off after dark with a mysterious lover.

Ivy worries her cousin could be in danger—especially after Heather is elected queen of the May Day celebration. When Heather goes missing, Ivy must come to terms with the fact that she never knew her beloved cousin—or Rowan’s Glen—as well as she thought she did.

Readers looking for horror, romance, and suspense will find it all in this chilling tale that resonates with dark beauty.

Excerpt

So you must wake and call me early, call me early, mother dear,

To-morrow ‘ill be the happiest time of all the glad New-year:

To-morrow ‘ill be of all the year the maddest merriest day,

For I’m to be Queen o’ the May, mother, I’m to be Queen o’ the May.

—Alfred Lord Tennyson

“The May Queen”

Now

Kerosene slopped from the rusty pail and splashed across the side of the barn. Fumes burned my eyes but still didn’t blur the sight of my father’s silhouette as he faced the barn, bucket in hand. The barn would burn down tonight and with it the remains of the body inside.

“Go to hell, you son-of-a-bitch!”

Dad’s voice ripped through my head. His shoulders twisted right as he wheeled around, sweeping the pail away from his body. More kerosene rained against the wood while everything in my gut scorched up my throat. I was too tired to get sick on the hay, my body wasted from screaming. I wiped my hand over my mouth when something snagged my lip. My fingernail was missing, a ragged root jutting out from the bloody bed where the nail had fought to hang on. When he bit it off, he swallowed the rest of it.

None of this is real, my mind promised.

Yet as clearly as I smelled the kerosene and felt the spring air and dust in my nose, my feet were firm on the ground. No matter how my mind ached to fly away, it was still tethered to a stark truth. This was real.

“Ivy, stay back,” Dad warned and then looked to Mom waiting close by with an antique lantern that shed little light. The night sky swelled with clouds like spiders’ egg sacs ready to burst, but the storm would miss Rowan’s Glen as all storms had. The hay, the ground, the very barn itself were kindling-dry, and every movement kicked up brown dust clouds. Mom pulled me back until we were safe from the kerosene tinderbox. The clink of her silver bangles racking together as she eased her arm around my shoulder jarred me into finding her eyes. They were the shade of a black walnut’s shell and equally hard.

“Don’t worry.” Maybe it was Mom’s still thick Mexican accent or my blood rushing through my ears making it hard to understand. Her expression stayed blank but for a pinch around her eyes. She tipped her head toward the barn. “This has to be done.”

I wadded my fingers into my long skirt. I no longer cared if the blood staining my fingernails smeared on the blue patchwork I’d stitched together last summer. My cousin Heather and I had sewn peasant skirts for the girls in the Glen. I loved feeling of my skirts flaring when I spun, round and round, always with Heather.

The skirts marked us. We looked different from everyone else in this hollow, from the rollers in the trailer park and the townies. They knew we were hillfolk because of our boys in trousers with suspenders and girls with long skirts. The last time I’d seen Heather, she’d worn a skirt with red ruffles.

Dad drew a trail of kerosene on the ground as he backed away from the barn. Once the pail was empty, he threw it inside. I couldn’t see into the shadows filling the barn. The body lying on the stone floor might yet have a pulse. And if it was, then I could be chased again. I stared at the kerosene soaking the ground. A shiver tugged at my neck, my chest rising and falling with shallow breaths. One clear thought pierced the muddle in my brain, and it made me sick.

I wanted the barn to burn.

“Timothy,” Mom called to Dad and fished a book of matches from a small pocket in her apron. “Use these. They burn up. Destroy the evidence.”

My father took the matches before stretching one hand potent with fuel to take mine. He was strong. My throat ached when I swallowed. He’d choked me, tried to silence me. Now I was quiet and stayed silent as Dad let go of my hand, struck the match, and threw it into the fuel snaking away from the barn.

The fire didn’t whoosh to life as expected. First, the match hit the ground and breathed for a moment. Then a blue worm of fire emerged from the earth and devoured one blot of fuel before moving to the next. Upon reaching the barn, the worm bloated into a dragon that flamed yellow and orange. The wood plank construction hammered by my great-great-grandfather when he was a young man crackled and popped, bone-dry from drought. With the fire now twisting through the barn, coils of smoke erupted from the windows. The pulse of the body inside thump-thump-thumped in my head. It ran over me, growing frantic. Dying.

“Mom?” I whimpered.

“It’s only fair,” she said.

Dad didn’t speak. Rage had made him do the unspeakable. For me, even though I’d survived. For the ones who hadn’t. Fire was cleansing. Fire was vengeance. The fire burned red, as red as the ruffles of Heather’s skirt. As red as Heather’s hair.